GR 20 2016

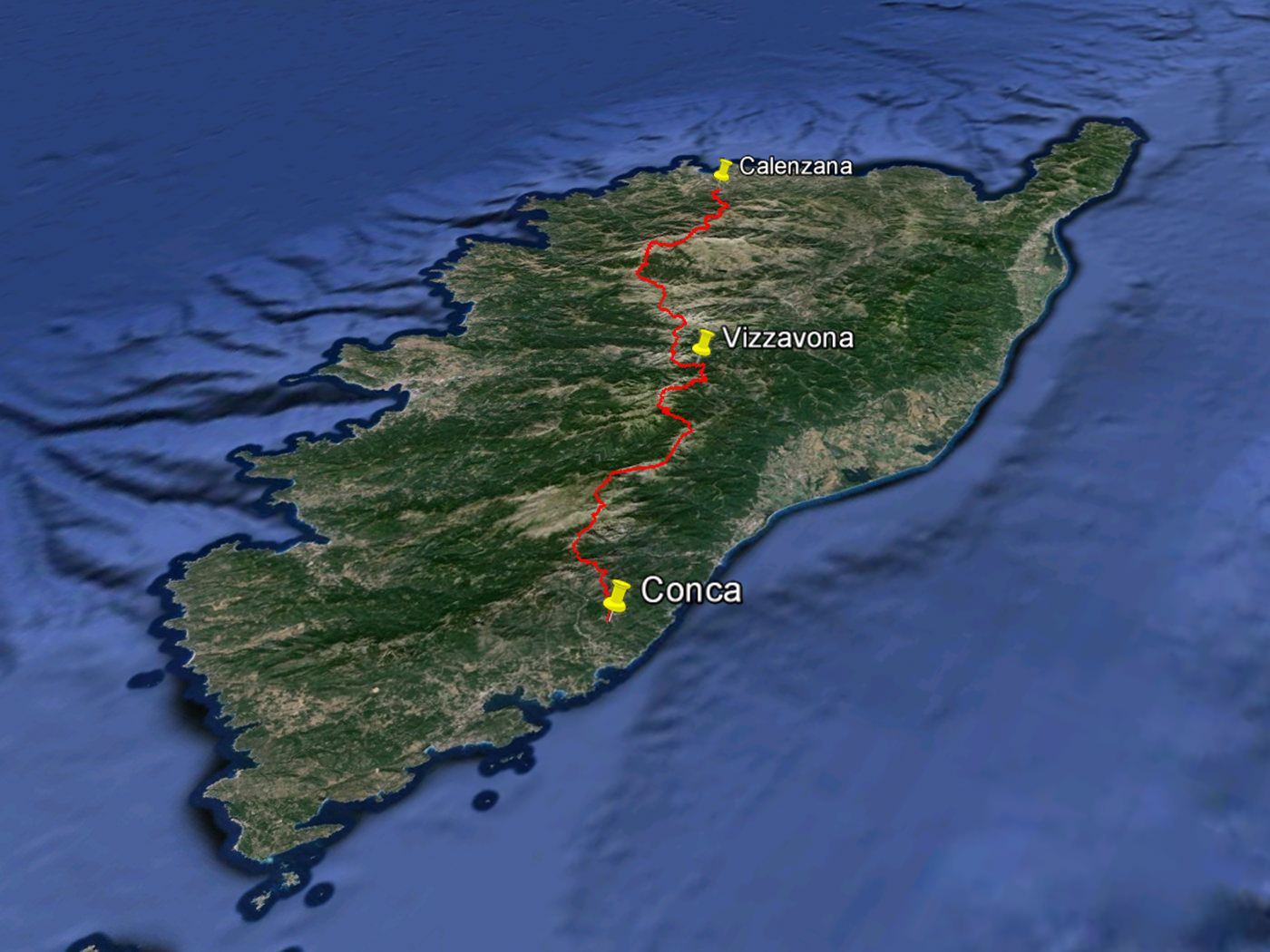

The GR 20 is reputedly the toughest of the European Grand Randonnée (GR) walks. It spans the length of Corsica north-south for 190 kilometers (118 miles) with a 12.500m (41,000ft) gain. It is divided into sixteen stages (étapes), with a refuge at each stop offering dormitory beds, camping spots, rudimentary meals and provisions. Between almost every étape there is a high route (variante) and a low route. The high routes are preferred for their vistas but are not advisable in stormy conditions or high winds. Several portions of the trail are class 3 type climbing, and there are a few class 4 steep areas that are sometimes augmented with chains. I choose to start the trail at Conca in the south on June 7, 2016, which in this year is the earliest one can start and make it through the snowy areas without the use of crampons and ice ax.

I fly into Nice with a planned 90 minute window to make it to my overnight ferry that will transport me from Nice to the start of the trail in Conca. The plane is late and I have only 45 minutes to clear customs and hightail it across town to the Quai.

I book a room for the overnight passage but am disappointed that I cannot open the windows for the sea breeze.

I choose to take the ferry to Corsica because it seems like the best way to decompress from a 16 hour flight and to provide the proper sea context for trekking on a Mediterranean island.

Sunrise, 5:49 am.

Suddenly my next two weeks come into view. Exciting.

7:30 am arrival at Porto Vecchio, easy walk to the 8:30 am bus to the bus to the trailhead at Conca.

A wilderness or outdoor natural area in the French language is called the "pays sauvage". That inflection of "savage" has always struck me as more threatening than any association I have with the words "wild" or "wilderness". The rocks do indeed seem "sauvage".

The red and white blaze marks ("balisages") will be my constant companions for the next two weeks. You trust them, you follow them, and if you go more than two minutes in the complicated rock areas without seeing them, you are likely off-trail.

An early water opportunity, Backstroke is pleased.

CLICK PANO FOR LARGER VIEW.

First night at the Refuge de Paliri. The dorms ("dortoire") are in back, camping off to one side. The dinners ("repas") are pleasant on the front decks that are a feature of most refuges.

Day 2. OK, this is good and getting better.

I am normally not a fan of user-inspired trail rock art and have been known to kick over excessive cairns. But once I accept that these rock piles are a feature of the trail, their variety and inventiveness become amusing.

Notre-Dame des Neiges. On...a rockpile.

CLICK PANO FOR LARGER VIEW.

First chain experience. In dry weather I might be capable of descending without the chain. In wet weather, no way. Nevertheless the rocks in the South have good grit and my Wildcat trailrunners have great traction on them.

It keeps becoming more "sauvage".

Second night at the Bergeries d'Asinau. Open air cold shower behind twig thicket.

Day 3. I am out the door at 5:30 and the first to reach the peak of Monte Incudine, 2134m (7001 ft). Note the red and white blaze balisage leading up the hill. This is what passes for a trail in many places on the GR 20.

Day 3 from Asinau to Usciolu is long, collapsing two étapes into one day. I climb 1315m (4314 ft) and descend 1034m (3391 ft).

I enjoy the sweeping vista in the descent from Monte Incudine.

The final few miles along the Usciolu crest is a tortured path up, over and around rocks, in the rain.

Day 4. A new day and another crest experience. Much more enjoyable when rested and with the sun shining.

My favorite picture of the trip. Unusual clouds rise quickly and unexpectedly when walking the high crests. One learns that a sunny day is no guarantee that clouds, fog and rain will not appear and change everything very fast. CLICK PANO FOR LARGER VIEW.

Night 4 at Col de Verde. This is the famous Corsican Fire Salamander, Salamandra Corsica.

Tyrrhenian Wall Lizard, Podarcis tiliguerta. There are about ten gazillion of these on the path, always moments away from getting stepped on.

Despite ominous weather reports, I do the high route variante and make a run for my third peak, Monte Renoso, 2352m (7715 ft). It is very exposed and if the weather were to turn bad, it would not be a good situation.

It takes some time and effort to get to Monte Renoso, increasing my nervousness about the exposed and precarious nature of the situation. In one of the guidebooks the writer Paddy Dillon advises that in bad weather "leave the mountains well-enough alone."

Day 6. The French tin-can prepared salads are good, and when fresh fruit is not available there is usually compote.

One of the oddities of the GR 20 are the many tissues neatly placed on the trail with a small rock to stop them from blowing away.

At the top of the pass at the Créte d'Oculo the wind blast is intense. I hear a woman exclaim "Étonnant" ("Astonishing"). I dive into the valley to the small town of Vizzavona, and my next day's destination is in view ahead, Monte d'Oro, a morning climb of 1489m (4885 ft.)

I identify more with the hikers and decide to camp instead of taking a room at the hotel. However Cormac, Libor and I dine there.

Day 7. I reach the peak of Monte d'Oro 2389m (7838 ft) with Christian, a young physics student from Munich. Ten minutes later the clouds roll in and the spectacular view disappears.

I reach the Refuge de l'Onda. The two men in the foreground are Thomas, hiking with his father Paul, both from Toulouse. The tents are enclosed in an animal pen which seems strange until one realizes that the fence keeps the animals away from the tents.

This is by far the busiest refuge encountered so far. The gardien is a funny character and the repas is good. The giggly British schoolgirl group I can do without.

Day 8. Up the hill to Refuge de Pietra Piana. These huts are for storing cheese in order to maintain a more constant temperature and humidity.

The wind is intense, and I lock down my tarp with everything available. It holds fine, but in the morning I have to replace every cord as they all frayed on the line-locs to near breaking point. There are very few tarps in evidence on the GR 20, and on several occasions with intense winds or rain I am asked by the French hikers if I am alright, as if there is something dangerous and insufficient about the tarp. I am super happy to not sleep in the dormitories, with all the close proximity, coughing, snoring, etc. Not to mention the bedbug outbreaks in past years.

Eighty percent of the hikers are French and a surprising number do not speak English. Everyone, I mean everyone, says "Bonjour" when passing on the trail. I am pleased that I am able to communicate fluidly with my rudimentary French; trail talk does not involve academic discussions about Proust or Baudrillard. I do not hear many of the words and exclamations that were common in my youth, like "Voila!" = (all purpose exclamation); "merde" = ("sh*t"); la vache! = (literally "the cow", used like "darn!"); "alors" = ("so!"). I do hear one old favorite "dégueulasse" = ("disgusting", "rotten"). Everyone uses the word "rando", short for "randonnée" ("hike", as both a verb and noun) and "doubler" = (to "double", as in walk two étapes in one day). The two newer common slang words are the adjective "sympa", short for "sympathique" ("nice"); and "franchement" ("frankly", "actually", "really", "for real", "literally"). Franchement is overused and used incorrectly in the same way that American kids use the word "literally" or "honestly". Franchement.